Chapter 12: Further Comments on Classical Optical Instruments

There was more interest in Chapter 3 about the classical instruments used for optical alignment than any other chapter to date, and I didn’t have a chance to say all I wanted to, so I will continue the discussion in this Chapter to emphasize how changes in technology have changed the design of these instruments. The instruments discussed previously are basically the same; they increase the angular sensitivity of the eye from about 1 minute of arc to something substantially greater by using two lenses of different focal lengths to increase the magnification of the eye.

The objective and eyepiece in a telescope change the angular extent of a distant object into an image that subtends a much larger angle as the nearly collimated light enters the eye from the eyepiece. A microscope is nothing more than a telescope with a short focal length lens out in front to make small objects look larger by the ratio of the microscope objective to the telescope objective’s focal lengths. In this case, the telescope objective is known as the tube lens in microscope speak.

In the 17th century, when the telescope and the microscope were invented, the only illumination source was natural light. The object was directly illuminated in the case of the telescope, or natural light was reflected on the object by an auxiliary plane mirror for the microscope. Starting around 1830, candles and other types of lamps were used with microscopes for illumination [1]. This type of illumination would be impossible to use with any optical alignment instrument because these are double-pass instruments that project a reticle pattern, such as a crosshair, and view it in reflection.

The use of a crosshair or reticle pattern started in the 17th century, and Robert Hooke is given credit for the invention [2]. A crosshair is easy to install in a single-pass telescope or microscope, such as an astronomical or transit telescope for surveying. For double-pass optical instruments, illuminating a crosshair for projection was impractical before incandescent bulbs became available. These were not even available in small enough sizes to install inside the instrument around the early 1900s. The Drysdale paper from 1900 describing the autostigmatic microscope in Chapter 3 is vague on the illumination source, a probable indication of using natural light.

Even with a useful-sized bulb, the bulb illuminated a frosted window inscribed with the crosshair, reducing the light available for viewing the crosshair. A clear window would make the bulb filament visible and make a distracting background. The relatively low level of illumination of the crosshair is what makes finding the return reflection from an autocollimator so difficult. This is why lab lights are dimmed, and a flashlight is pointed down the eyepiece on an autocollimator to aid in finding the return reflection, and in this case, the alignment is just in two degrees of freedom.

[Sidebar] Before going further about the design of classical optical alignment instruments, let me mention a classic publication about them: Optical Instruments and their Applications, By Douglas F. Horne, published in 1980 by Adam Hilger, Ltd. The book goes into detail with chapters about telescopes, microscopes, cameras for commercial and industrial purposes, surveying instruments, aerial photography and photogrammetry. The chapter on Engineering Metrology covers the instruments I reviewed in chapter 3, alignment telescopes and autocollimators, and the tooling used with them, such as right angle squares and angle gauge blocks, but curiously omits autostigmatic microscopes. Many pictures of the optical paths in these instruments show how the reticles are illuminated. Unfortunately, the book is out of print but may be available in some libraries.

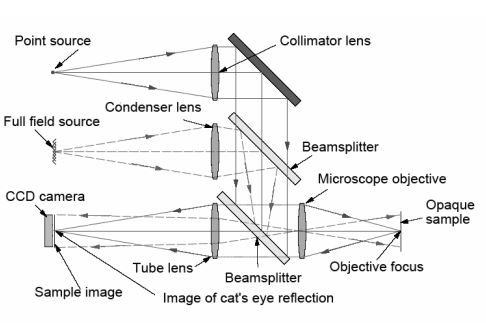

Once the laser was invented in 1960, the lack of a bright light source was solved. Further, coupling a laser to a single-mode fiber produces a near-perfect spherical wavefront. When this spherical wavefront is collimated, a plane wavefront is created that is useful for autocollimators. This wavefront is reimaged as a several micrometer diameter spot on the detector in the autocollimator, leading to sub-microradian angular sensitivity when coupled with a sufficiently long focal length collimating lens. A 100 mm focal length autocollimator has a 1-2 µradian sensitivity using a CMOS camera as a detector.

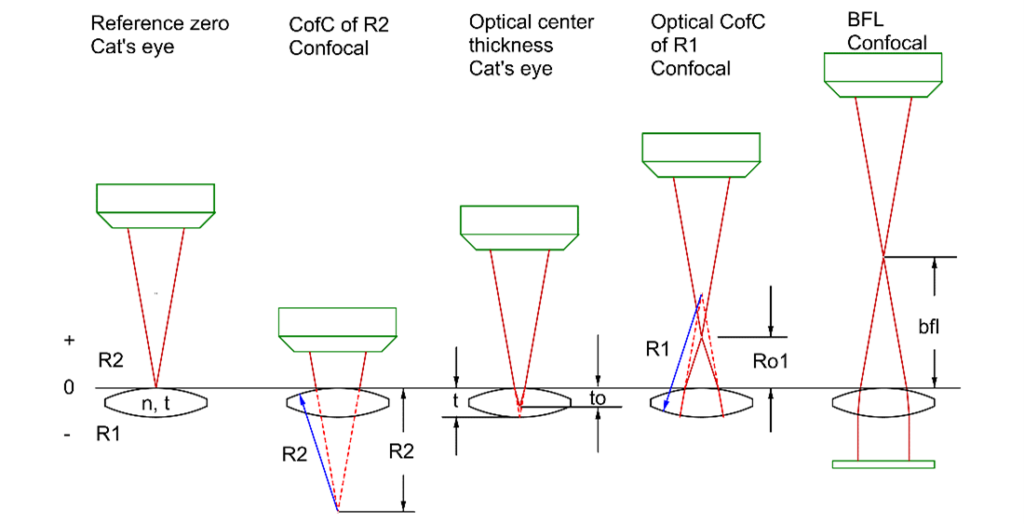

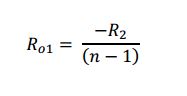

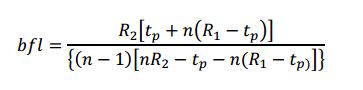

In addition to the laser/fiber combination increasing the resolution, the higher brightness makes the initial alignment of the mirror to the autocollimator easier because the reflected beam is more easily seen under ambient lighting conditions. This angular alignment only concerns two degrees of freedom. To align an autostigmatic microscope that can be thought of as an autocollimator with a microscope objective added on the front, see Figure below, three degrees of translational freedom are involved. This requires even more light to find the location of the reflected spot and get the spot in the small volume of space that the detector can see.

It may seem counterintuitive, but the axial degree of freedom is the most difficult to locate. This is because the focused cone of light spreads out, and its intensity varies as the square of the distance from focus. One must be in the correct axial position to a mm or so to see the focused spot using a 1 mW laser under ambient lighting.

As with the autocollimator, as soon as just a bit of the reflected light enters the microscope objective, the alignment is easy to finish. In fact, with modern digital detectors, the 1 mW source is orders of magnitude too bright to avoid saturated pixels when the reimaged spot is in focus.

In a carryover from past instrument designs, most current autocollimators and centering equipment display an electronic crosshair that simulates what you would see looking into the eyepiece of an older instrument. I prefer to look at the reflected spot image itself because the spot contains information lost with the simulated crosshair. As little as a 10th wave error in the surface being viewed will distort the reflected, nominally perfectly circular spot. Because of this, it is immediately obvious if something is wrong with the object being viewed.

I remember long ago viewing a 300 mm diameter spherical mirror at its center of curvature. The technician behind the mirror adjusting the mount to align the center of curvature to my autostigmatic microscope was surprised when I told him the mirror was too tightly clamped. He said, “That can’t be; it’s only finger tight.” I had him look at the image of three distinct flares at 120° apart. He shrugged his shoulders and said, “Oh,” and went back and loosened the mounting screws.

More recently, much the same thing happened in a government lab using a point source microscope (PSM). The user thought something was wrong with his PSM and had sent me a picture of the image. I suggested he check the mount, and he found that it was the mount, not the PSM, that was at fault. These are examples of situations where if the problem is misunderstood, the error can creep into work farther down the line, where it is even harder to figure out what went wrong. It is much better to find out early, which is easy to do if viewing the real image rather than a simulated crosshair.

[Sidebar] A good reference for looking at images (and that is in print) is Star Testing Astronomical Telescopes by H. R. Suiter, published by Willman-Bell, Inc. (1997). The book has many photographs of star images through focus and of misaligned, poorly mounted and roughly polished surfaces. This gives you a good idea of the kind of images you can see in an autostigmatic microscope that uses a single-mode fiber as a “star.”

There is an additional benefit to directly viewing the reflected image. The same sort of software that aids in aligning astronomical telescopes can be used with a fiber or pinhole-illuminated autostigmatic microscope to give quantitative wavefront information. Here I refer you to

https://www.innovationsforesight.com/product-category/software/skywave/

To recap, the optical principles of modern optical instruments are no different from those used 200-300 years ago. What is different are the sources of illumination, orders of magnitude more intense (the laser or LEDs), and more spatially controlled via optical fibers, computer-generated patterns, and spatial light modulators. On the receiving end, digital cameras are many times more sensitive than the eye. Because of a large range of shutter control, they work well over orders of magnitude of incident intensity. Combining a high-brightness source and the ability to control that intensity at the detector gives modern optical alignment instruments a sensitivity and flexibility that is impossible using the eye as the detector.

In future chapters, we will cover additional flexibility provided by the analysis of structured illumination to provide a third dimension of information from nominally two-dimensional intensity distributions.

[1] Davidson, B. M., “Sources of illumination for the Microscope 1650-1950”, Microscopy, 36, pp. 369-86, (Jan-June 1990)

[2]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reticle#:~:text=Most%20commonly%20associated%20with%20telescop ic,dates%20to%20the%2017th%20century.