Chapter 20: Aligning Off-Axis Parabolas with a Bessel Beam — It’s Much Easier

Introduction

In Chapter 18, I described aligning off-axis parabolas (OAPs) by placing the focus of a test instrument at

the OAP’s focus and autoreflecting off a plane mirror. Although I suggested some tips to ease the

process, the initial alignment—getting the reflected light back into the test device’s objective—remains

challenging.

Because I’ve found that using a Bessel beam makes lens alignment easier, I wondered if the same would

apply to OAP alignment. (Spoiler alert: it does!)

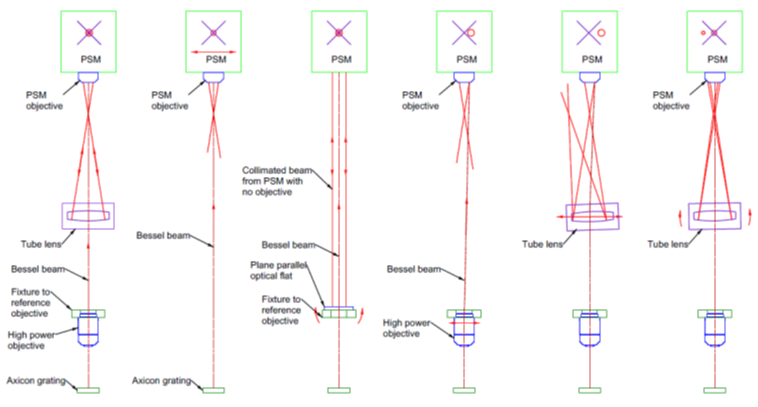

Initial Alignment

I started with an Edmund Optics 25 mm diameter, 15° OAP with a 387 mm effective focal length (EFL). I

projected a Bessel beam (BB) roughly along the optical axis toward the OAP and viewed the reflected

beam with a Point Source Microscope (PSM) about 400 mm away. The reflected beam was clearly visible

on a white card, which made it easy to position the PSM so the beam was centered on the 4x objective.

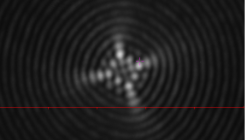

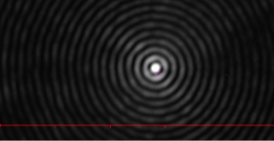

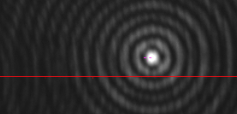

See Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 shows the initial image. The image width is about 40 µm, across a 100 µm field of view.

Why the Bessel Beam Helps Initial Alignment

Using a BB simplifies initial alignment for two main reasons:

1. Two Degrees of Freedom – You’re locating a beam-like spot instead of a focused point, so you

only need to search in two dimensions rather than three. You can find the spot anywhere along

the beam.

2. Single Pass Simplicity – The BB allows single-pass alignment rather than a more complex

double-pass process. Once the spot is in the objective, you can immediately begin minimizing

aberrations by reducing the BB pattern’s size.

Fine Alignment

The most noticeable feature of the image in Fig. 1 is its rotation relative to the test coordinate system.

It’s easier to reduce aberrations or spot size consistently if the image is squared with the axes. This is

done by translating the OAP parallel to one of the axes while applying compensating tilts to keep the

spot centered.

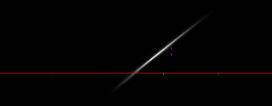

Fig. 2 shows the result after squaring the image.

Once the image is squared, as in Fig. 2, you can use the orthogonal axis adjustments to reduce the image

size. Large changes help determine the correct direction to minimize the image. As you progress, fine

adjustments eliminate residual misalignment as in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3 shows the final aligned image.

The Alignment Experience

I was surprised at how easy the alignment turned out to be. Here's why:

- The reflected spot was easy to find.

- Only two adjustments—tilt and decenter—were necessary for full alignment

- Focus adjustments weren’t needed since the BB always appears in focus.

- Progress was easy to monitor: the number of bright spots in the BB image decreased asalignment improved.

- While aligning an OAP still isn’t as easy as finding the center of curvature of a sphere, it's not much

harder.

Aligning a 90° OAP

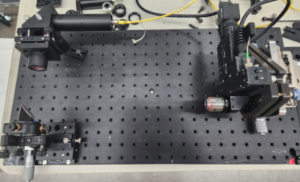

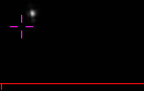

Encouraged by the 15° OAP results, I tried aligning a more difficult 90° OAP with a shorter EFL. The setup

(shown in Fig. 4) was similar. The BB projector was aimed roughly along the OAP axis, and the PSM was

placed several focal lengths away—not near the focus.

Fig. 4 Alignment setup for 90° OAP (lower left) in an adjustable mount, a Bessel beam projector (upper

left) pointing along the OAP axis and a PSM (right) several focal lengths from the OAP.

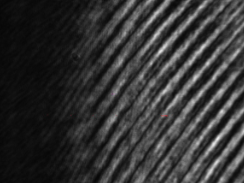

After roughly mounting the optics, I turned on the BB source. Even when the core of the BB image was

~15 mm off-center from the 4x objective, the PSM still picked up the pattern (Fig. 5). This again

highlights the advantage of the BB: the outer rings offer clear visual cues for centering adjustments.

Fig. 5 Initial image seen by the PSM with beam Fig. 6 Initial image after centering the core on the

15 mm from the center of the objective PSM (Both pictures show the uncropped images)

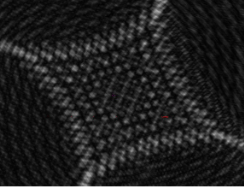

Fine Alignment of the 90° OAP

The 90° OAP image was larger than the 15°, which makes sense given the lower f/# (f/2 vs. f/15). The

shape and initial misalignment were similar in both cases. After squaring the image to the adjustment

axes, fine alignment was straightforward, as seen in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7 Aligned BB image from 90° OAP

Comparing Figs. 3 and 7:

- Both are shown at the same scale (100 µm bar).

- The BB core in Fig. 3 is about 3× smaller than in Fig. 7.

- Fig. 3 has ~8 rings, while Fig. 7 shows ~4—evidence of the different f/#s.This scale difference deserves further exploration in BB-based alignment.

Verifying Alignment

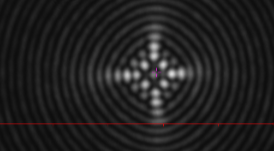

Of course, you shouldn’t just take my word for it. To confirm alignment, we can examine the double-

pass image at the OAP focus.

The BB projector was initially aligned to propagate normal to the grating, ensuring that the BB was

aligned with the OAP axis. Moving the PSM to the OAP’s focus, its internal point source illuminated the

OAP, and the collimated light reflected back through the BB grating.

Because of physical interference between the PSM and BB projector at close range, I had to move the

OAP slightly (see Fig. 4), then realign it.

The initial double-pass image (Fig. 8) was slightly astigmatic—about 50 µm long—suggesting ~8 µm

defocus (4 µm in single pass). A small tweak produced the near-perfect image in Fig. 9, where the image

size matches what I see when aligning to a Grade 5 ball—suggesting a wavefront error of ~1/8 to 1/10

wave.

Fig. 8 Initial double pass image at the OAP focus (Same scale as other cropped images)

Fig. 9 Double pass image from 90° OAP at scale, and zoomed in. The space in the middle of the crosshair

is 11 µm so the image is about half that, and half again for double pass.

Discussion

Aligning off-axis parabolas becomes much easier using a Bessel beam as a reference axis. Key

benefits include:

- Ease of Beam Tracking – You can see the BB spot at almost any distance.

- Straightforward Progression – Once the image appears on the detector, alignment is

just a matter of tilt and decenter. - No Focusing Required – The BB is always in focus, so you can focus on making the image

smaller and more symmetric. - Visual Feedback – The decreasing number of bright spots in the BB image gives

immediate feedback on alignment progress.

If you’re using a PSM, you can finalize the alignment by moving it to the OAP focus and checking

the double-pass image off the BB projector’s grating. This confirms both BB and OAP

alignment—and, assuming the OAP is of good quality—produces a diffraction-limited result.

I hope this note helps those of you who have struggled with the frustrations of aligning off-axis

parabolas.